|

Mar 26,2006 - Apr 2,2006 |

8 - "La Merica" proved hard and generous

Italian immigrants flocked to San Francisco during and after the Gold Rush of 1849

By Antonio Maglio

Originally Published: 2002-09-15

|

|

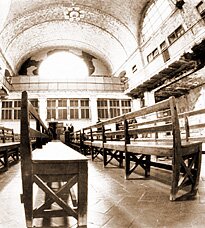

The arrival hall at Ellis Island in New York harbour

|

In the spring of 1847, Andrea Gagliardo - a peasant from the countryside near Genoa - sailed on his first trip to the United States. He would eventually go back and forth 14 times, until 1888, when he finally returned to his hometown. His diary tells us how far was la Merica. Gagliardo wrote: "1847. On board the brig Bettuglia. Genoa to New York: 57 days". For two months, sky and sea, sky and sea.

We don't know how much Gagliardo paid for the crossing, but certainly no less than 300 lire (a fortune): that was the price for a Genoa-Buenos Aires cruise. Considering that the average ship could load 700 to 1,000 passengers, figuring out the profit for the shipping companies, which charged cargo at 290-300 lire per metric ton: the price of a ticket. Of course, no man weighs a ton.

The shipping companies weren't the only ones to profit from the human flood that crossed the ocean from the mid-19th century onwards. Up to 1901, when the Italian government passed a law regulating emigration, this was left in the hands of unprincipled private agents, "a new race of slavers, not unlike the old as to greed and lack of scruples," as they were called in an 1885 report from the Statistics Office of the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Trade.

They were connected to the shipping companies, and on their account they toured the bars and country fairs, wherever they could find people who would listen to them, and praised the comfortable crossing and the opportunities awaiting in America. They went beyond this, though: "They lie as in ambush, waiting for misery to grow in a given family," reads another report. "They know when the mortgage of farmer Tom is due or whether Dick the worker is indebted to a loan shark. Then they seduce, propose, insist, over and over, especially in the off season, until they manage to get one's assent to expatriate." They were paid a fee on every emigrant that boarded a ship.

Private individuals were not alone in this: mayors and parsons, town clerks and teachers, pharmacists and even some retired Carabinieri marshals: "All of them," underscores Amoreno Martellini, a scholar of emigration, "could spend the respectability deriving from their social role in order to supplement their income with the revenue of the fees on the emigrants."

Page 1/...Page 2

|

| Home / Back to Top |

|

|

|

|

|